Why should I listen to the Catechism?

In response to an argument about the death penalty

“Thou couldst have no power at all against me, except it were given thee from above: therefore he that delivered me unto thee hath the greater sin.”

John 19:11

I’m so sorry I have not been able to write here for so long. I have been going to college studying Petroleum Engineering, and that takes up a lot of my time. However, in that time I have argued with many people—a perfect way to prepare me to write an article.

This article is responding to a series of arguments I have had this semester about the authority of the Pope, and the infallible teachings of the Catholic Church.

Dr. Peter Kwasniewski in his essay What Good is a Changing Catechism? Revisiting the Purpose and Limits of a Book discusses the history of the different Catechisms and the concerns about the changes made to them, in particular the death penalty. I will draw a lot from his work here. If anyone wants to go deeper than I did, he would be a great place to start.

I know there are quite a few non-Catholic readers on this Substack, so I will make sure not to be too technical in my writing (I hate that anyway).

Btw, y’all should become Catholic.

Also, I think I need to clarify something quickly:

Small essay

Papal Infallibility

By Boniface

Infallibility is not something that the pope exercises whenever he feels like it. It’s not a holy “gut feeling”. In fact, in down-to-earth terms, something is infallible if it can be traced back throughout Church history through time. If the pope came out and said “abortion is Church teaching”, that would not be protected by infallibility since it cannot be found anywhere else in Church Tradition.

End of small essay.

Anyway, the argument that I will start with (and hopefully springboard off of) was about the Death Penalty, and whether it is permissible under Catholic teaching.

Here is the argument that was posed to me, as far as I can remember1:

It is wrong to take the life of another person. In previous times, when high-security prisons were not prevalent, the death penalty was a necessary evil. In this day and age, however, it is immoral given the existence of high-security prisons.

In addition, this argument was strengthened with a quote from the Catechism of the Catholic Church:

I am a little confused as to why this corroborates the other argument. They were offered to me at the same time by different people, and I am trying my best to recollect and present them as accurately as I can.

—CCC 2267 (the most recent 1997 edition but updated, as we will talk about later)

Now, I had always been taught that the Church left the question of the death penalty to the prudential judgement of the state. This always seemed to me to be a reasonable way of explaining it: the Church cannot know the circumstances of every legal case in every society for all of time, so they instead provide general guidance and leave it up to the civil authority.

I was told, however, that the Church has since clarified this teaching. This did not sit well with me, so I went back and looked at our home Catechisms and lo! I was right! This puzzled me and sent me down a rabbit hole where I spent a lot of time that I could have used getting ready for finals.

So, without further ado, here is my defense of the death penalty.

I feel that the prisons argument is the less important of the two, so I will just say one thing and leave the rest in this footnote2:

The death penalty is NOT for getting rid of problematic prisoners or making sure that the dangerous prisoners don’t escape or influence their buddies on the outside. In fact, almost every Catholic argument that I have read (which I will list later) that advocates for the death penalty comes from the perspective of justice. In other words the state must apply the just punishment for the crime committed, and extremely serious crimes incur death as a punishment.

With that out of the way, I will start with the Roman Catechism from the Council of Trent, which says that:

Another kind of lawful slaying belongs to the civil authorities, to whom is entrusted power of life and death, by the legal and judicious exercise of which they punish the guilty and protect the innocent.

In addition, the Baltimore Catechism (Q. 1276), and the Catechism of St. Pius X (5, Q3) both corroborate this statement, along with many others. Given that these citations are from 1566, 1885, and 1908 respectively, there is a case to be made that this is said in union with the Magisterium of the Church, and is therefore infallible.

Secondly, we can strengthen this statement by looking at the saints. It is commonly believed among Catholics that St. Thomas Aquinas is the greatest theologian of all time. In his Catechetical Instructions, he touches on the death penalty, saying that:

“…thus that which is lawful to God is lawful for His ministers when they act by His mandate. It is evident that God who is the Author of laws, has every right to inflict death on account of sin. For ‘the wages of sin is death.’ Neither does His minister sin in inflicting that punishment. The sense, therefore, of ‘Thou shalt not kill’ is that one shall not kill by one's own authority.”

In addition, St. Augustine, the challenger to the GOAT status of Aquinas, says in his City of God:

“However, there are some exceptions made by the divine authority to its own law, that men may not be put to death. These exceptions are of two kinds, being justified either by a general law, or by a special commission granted for a time to some individual.”

If that were not enough, Pope Innocent I in 405 defended the death penalty in one of his letters.

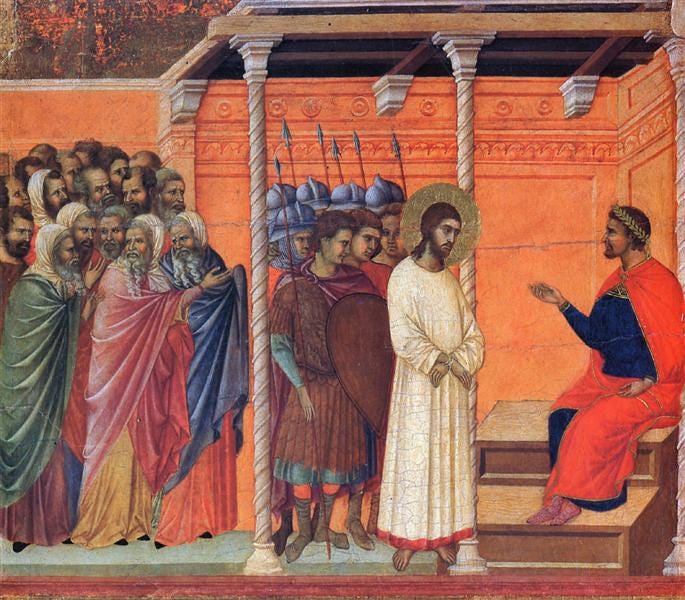

So, we have Catechisms and Saints defending the death penalty. The final leg of my defense is quoting the Bible. The best quote I could find is the one I began with from the Passion of St. John, when Jesus is in front of Pilate:

“Thou couldst have no power at all against me, except it were given thee from above: therefore he that delivered me unto thee hath the greater sin.”

Jesus says that the civil authority gets his power to execute from God (we can talk about the consent of the governed and the divine right of kings later). In this case, of course, the power is being used against the innocent, but Jesus never questions Pilate’s power.

The words of St. Dismas (the “good thief”) at the Crucifixion presents the death penalty as a mean of enacting justice for crimes:

“But the other answering rebuked him, saying, Dost not thou fear God, seeing thou art in the same condemnation? And we indeed justly; for we receive the due reward of our deeds: but this man hath done nothing amiss.”

Again, Jesus does not answer by declaring that the punishment is immoral. He does not say “you guys should not be on the cross either”.

When Aquinas speaks on the death penalty (such as in the Summa or his Catechetical Instructions), he lists a series of verses that apply to his argument, such as:

“Wizards thou shalt not suffer to live” —Exodus 22:18

“In the morning I put to death all the wicked of the land.” —Psalm 100:8

“the wages of sin is death” —Romans 6:23

“For if thou dost that which is evil, fear; for he beareth not the sword in vain. Because he is God’s minister” —Romans 13:4

There are many more verses throughout the Bible that have been quoted as authority on this issue.

Given that the Bishops, Saints, and Holy Scripture seem to agree on this issue of the death penalty, we are met with a dilemma:

Who is correct, the current pope or the Magisterium of the Church?

Keep in mind, this is not a question of denying the legitimacy of the current pope. I do not want to look in the comments and see the word “sedevacantist” (which is the Catholic version of “racist” or “nazi”). The pope can (and will) be wrong about things. He is still only a man.

In this case, I would argue that given the pope’s contradiction of the historical teachings and Tradition of the Church, his stance on the death penalty as being against human dignity is opposed to Catholic teaching.

However, while the issue of the morality of the death penalty is what first presents itself, the real problem with the quote from the current Catechism (the first one above) is that it impacts our understanding of infallibility, Magisterium, Tradition, and the purpose of a Catechism.

This is because that quote from the current online version of CCC 2267 marks a complete change from what the Church has taught in the past, as opposed to the print editions that my family has.

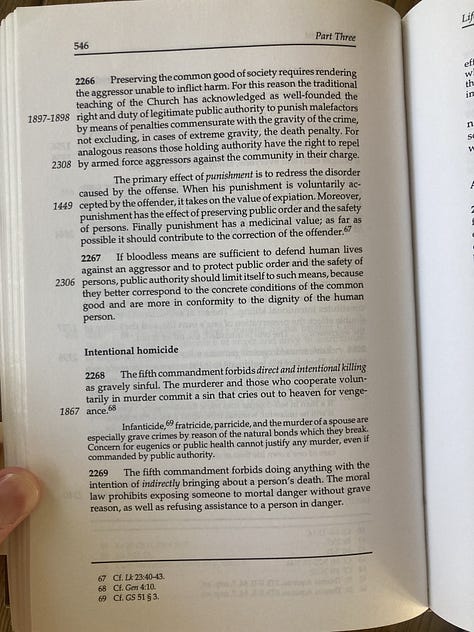

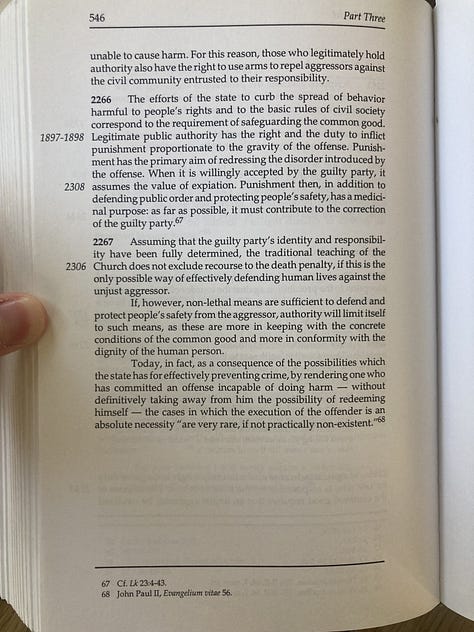

To illustrate this, look at the pictures from these three editions of the Catechism of the Catholic Church:

The first quote is taken from the first edition of this Catechism from 1994 (there are different Catechisms, as we will discuss later). The middle quote is from the 1997 second edition, while the final quote is from a 2018 re-release of the same second edition. The reason the pictures differ is that the 2018 came directly from the USCCB website, where it is listed as the default Catechism.

But the real problem here is not that they are rewriting the Catechism (though that is cause for concern). It is that the teaching itself changes 180 degrees over these three editions.

In English, here is what each Catechism is saying:

1994: Death penalty is okay, but try not to use it.

1997: While the death penalty is allow, there are so many alternatives that you don’t really have to use it.

2018: The death penalty is immoral and defies the dignity of the person

Can you see the flip? This is concerning, since actual teachings of the Church do not change.

Some people will just chalk this up to St. John Henry Newman’s Development of Christian Doctrine writing, which states that while doctrine does not change, it gets better clarified as time goes on3. On the contrary, this is exactly the opposite of what Newman was talking about.

“A true development, then, may be described as one which is conservative of the course of antecedent developments being really those antecedents and something besides them: it is an addition which illustrates, not obscures, corroborates, not corrects, the body of thought from which it proceeds; and this is its characteristic as contrasted with a corruption.”

—An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, page 200

In short, true development is only when if further clarifies an existing teaching that existed before, not a contradiction of what has been historically taught.

We are faced with two Catechisms that are disagreeing, not clarifying, with each other. Which is correct?

This all begs the question: is it possible for errors to appear in a Catechism? There are only two answers to this question:

No, each Catechism serves to clarify the teachings of the last, and you need the most recent edition to stay up to date (which begs another question).

Yes, Catechisms are fallible, and if there is contradiction, the way to find the answer is to look at what the Magisterium and Tradition have said over the centuries through previous Catechisms, Church Councils and documents, Sacred Scripture, and the writings of the Saints.

In my humble opinion, it is the latter. I find no evidence or statement that a Catechism (not the infallible teachings quoted in their correct context but the book itself), no matter how official, is free from error—especially if you keep on having to change it.

In fact, we have examples in history of bad Catechisms. An example is the Dutch Catechism of 1966, which was the first post Vatican II Catechism. The Vatican ordered the Dutch bishops to retract the book in 1972 because of it’s errors. Note, this was not some random priest going off and writing a bunch of bunk, this was a major publication endorsed by Dutch bishops that sold millions of copies.

This leads me to the conclusion that the only way to read the current Catechism is in light of previous Catechisms (along with Church Councils and documents, Sacred Scripture, the writings of the Saints, and all that good stuff).

While the Catechism is a good document that can help the faithful understand the Faith, it does not stand by itself as infallible, and is not necessary for salvation.

Whenever I see the word “today” (as is seen in the 1997 and updated 2018 versions), it signals to me that this is not a timeless teaching of the Church. That word is inherently time-bound, it comments on things that did not apply before, but are happening now.

If the Catechism is not wholly timeless, then there are times when whoever is talking (whether it is a Pope or Bishop or whoever is writing it) is not speaking in unison with the Magisterium of the Church throughout time (which is one of the requirements for infallibility). A pope from the 1500s could not possibly be able to comment on the prison technology in the 21st Century, so we are ultimately left with the current pope’s opinion (whether it is JPII or Francis). And that opinion is subject to bias.

“Thou couldst have no power at all against me, except it were given thee from above: therefore he that delivered me unto thee hath the greater sin.”

John 19:11

These statements made about God and his Church have not been evaluated by Heaven or The Catholic Church. They were made by an 18-year old young man who likes to write. They are not guaranteed to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any spiritual condition or disease, nor are they guaranteed to be worded in the best and most accurate way. Please consult with your own priest, the Church, or God himself regarding the statements and analogies made in this article.

It came about because we were talking about whether Trump was a good candidate for Catholics to vote for, and his stance on the death penalty was put forward as a reason not to vote for him, which I took issue with.

“…if a man be dangerous and infectious to the community, on account of some sin, it is praiseworthy and advantageous that he be killed in order to safeguard the common good…”

To be fair, the argument about prisons is about the common good, and Thomas Aquinas agrees with that. It is not all about justice. He does not, however, take away power from the civil authority to decide what is in the common good.

If we look at the history of the death penalty and high-security prisons, I would argue that our current system is not as secure as ones before. The use of cell phones in prisons is very common (although being banned). In addition, even maximum security prisons allow for visitors. If we are just looking at the protection of society, these things could pose a threat, since a prisoner can still commit acts of violence or even order a hit in today’s prison system.

At least in medieval times (when the death penalty was not only a common but a public affair) prisoners could be sent to dungeons and forgotten about—a more secure but arguably less humane system than today.

In other words, the argument against the death penalty given the security of our prison system is not convincing when compared to prisons systems of earlier periods.

People use this same argument to say that immoral practices like gay “marriage” are okay by Church teaching.

Thank you, Boniface, great stuff, I loved it!